Finding Hope for a Queer Future

“I don’t want tomorrow. It’s a bad word.”

—Lillian Hellman, The Children’s Hour

When Lillian Hellman began writing The Children’s Hour in 1933, she was inspired by an essay written by William Roughead titled “Closed Doors, or the Great Drumsheugh Case.” This essay chronicled a nineteenth-century case in Edinburgh, Scotland in which two women found themselves dealing with an accusation, manufactured by a child within their own schoolhouse, of intimate relations with one another which led to social and financial ruin. Shifting from a legal case in the 1800s to one worthy of the dramatic stage in the early 1930s leaves one to wonder—why does Hellman choose to adapt this story, and why is it still performed today?

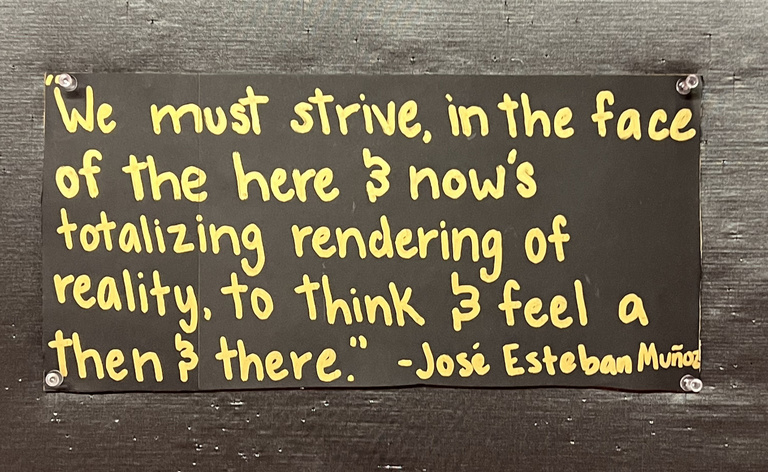

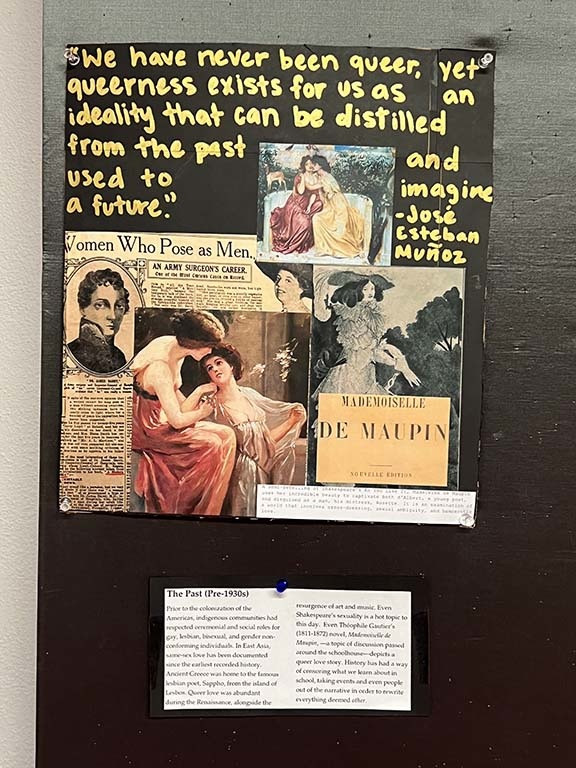

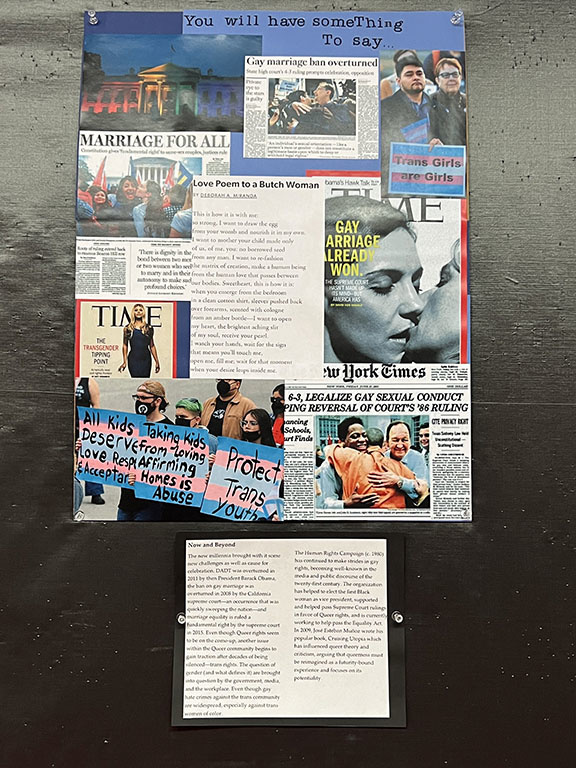

It is no secret that the media—literature, film, television, etc.—has a history of killing the only explicitly queer person within a story, often correlating directly with their admission of feelings. Since The Children’s Hour adheres to this “Bury Your Gays” trope that still seems to rear its tired head today, is it possible to use Hellman’s play as a way of filtering trauma in order to find this queer utopia that we desire? In his novel, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, José Esteban Muñoz notes that “queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future.” Experiencing our utopic habitat within the context of Hellman’s domain allows us to physicalize and examine this methodology of inciting hope and the potentiality for a queer future that challenges its place in the world of the play. The presence of our contemporary house demanding to be seen in Hellman's seemingly censored and restrictive world pushes us closer and closer to the edge of our seats as we attend to the past “for the purposes of critiquing a present” which, in turn, illuminates the path towards queer futurity.

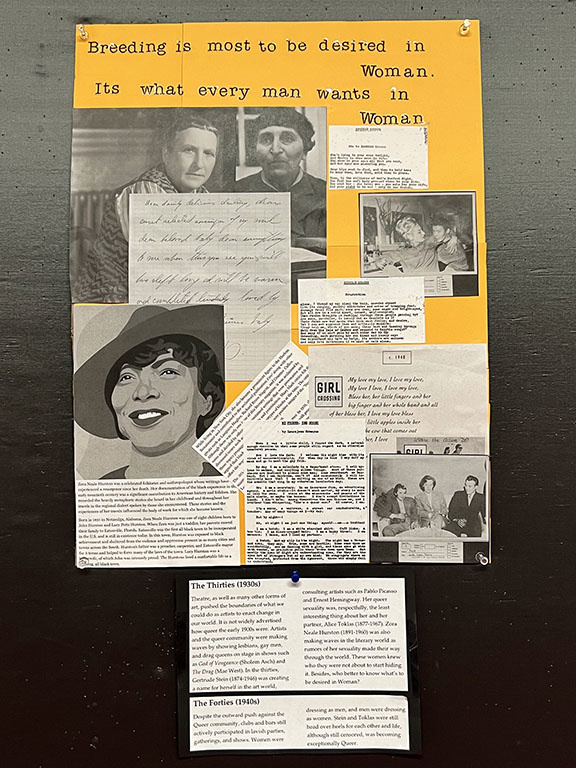

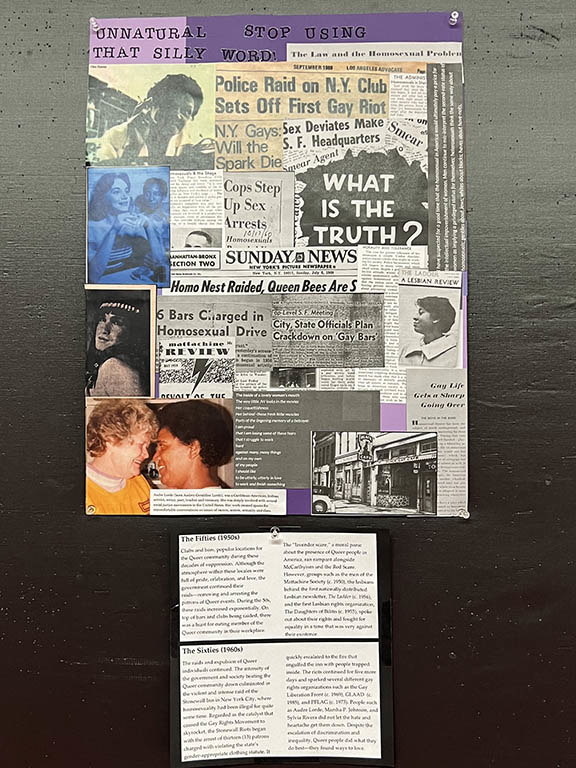

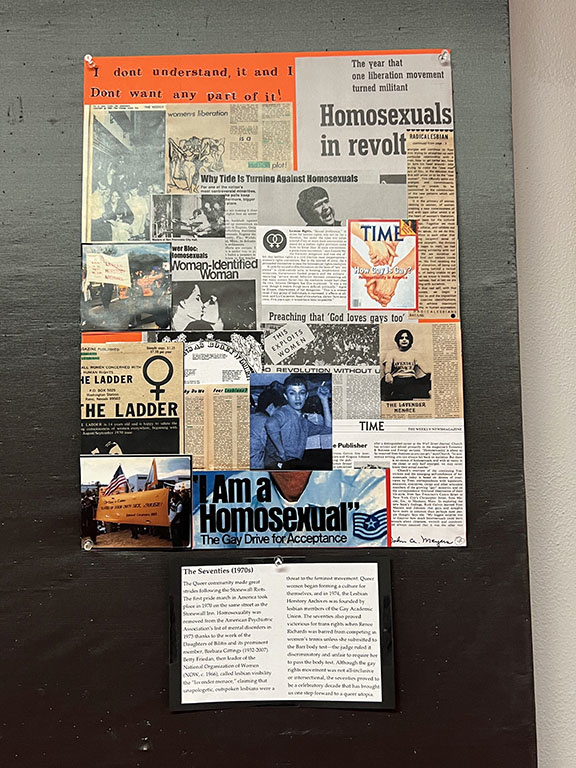

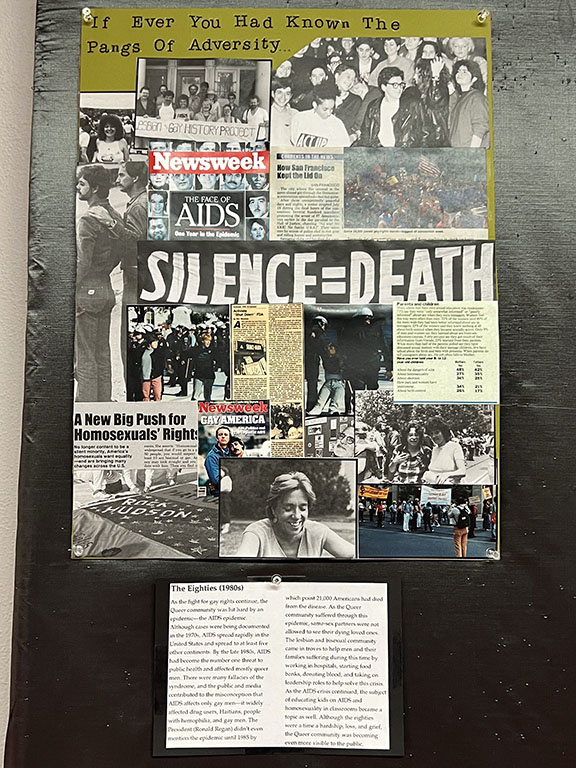

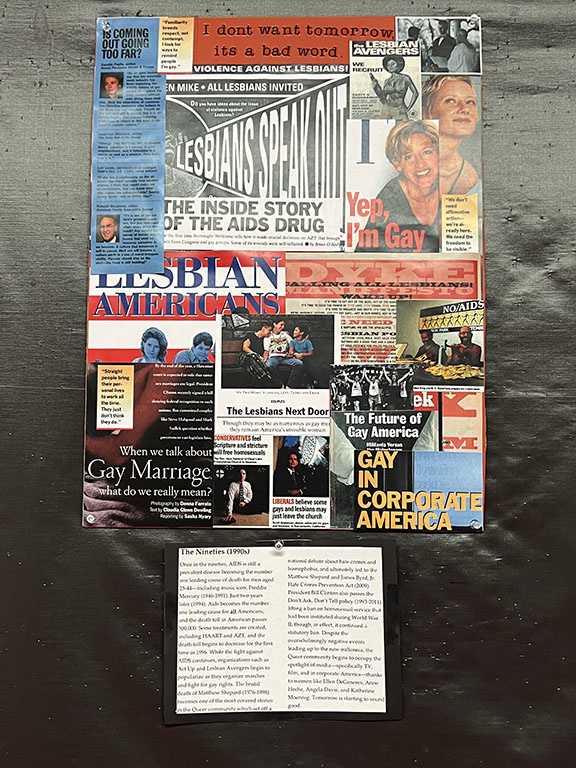

Queer rights have come a long way since Hellman sat down to write The Children’s Hour. However, the situation in America concerning queer and trans rights seems to be in a permanent state of flux. From laws banning children from transitioning to prohibiting the inclusion of anything queer in classrooms, this unpredictable atmosphere can make a queer future seem impossible—especially when society, media, and the government are constantly reminding us of the dismissive atmosphere that has surrounded queer stories for centuries. In exercising Muñoz's theory of using the past to examine the present, the University of Iowa’s Department of Theatre Arts aims to show how far society has come and how far we have left to go because maybe tomorrow will bring with it a new, hopeful dawn in which we are “future bound in our desires and designs.”

—Rebecca Weaver, dramaturg